How to Design a Closed-System Terrarium

Terrariums are beautiful interior accents for spaces where people live and work. Their glassy containers are eye-catching and draw viewers into the jewel-like plants they contain. They offer a miniature ecosystem—a window into the natural world. Humans possess biophilia, a natural, inborn love of nature. While today’s lifestyles may not allow us to be outdoors as much as we might like, terrariums give us a small way to experience nature’s unique flora. Just as important as a lamp or painting in creating a focal point within a room, terrariums are living sculptures that can practically care for themselves.

Any clear glass or plastic container is suitable for use as a terrarium. Some examples include fish bowls, canning jars (both large and small), and antique milk bottles. This, of course, is not an exhaustive list. The only essential consideration is that the container should not be cloudy or tinted, as this would restrict light and limit plant growth.

Types

There are two types of terrariums, characterized by the selected container: open systems and closed systems.

Open-system terrariums use a container with a wide opening, such as a large glass bowl. They typically need to be watered more often than closed systems and have lower humidity levels. A current trend is to use succulent plants or cacti, which are native to dry, arid regions and have a longer display period in an open-system terrarium. Plants from both lists at the end of this publication can be maintained in open-system terrariums.

Closed-system terrariums use a closed (or nearly closed) container. A lidded jar or a jar with a narrow mouth works well. These containers sustain the ecosystem necessary for moisture- and humidity-loving plants. However, this type of container is not suitable for succulents or cacti, as they would quickly rot and die in such conditions.

Closed-system terrariums can be surprisingly easy to maintain once their ecosystem is established. For that reason, this project outlines a closed-system terrarium.

Find a Display Site

Before purchasing plants and supplies, consider where the terrarium will be displayed. It’s a good idea for it to blend with the interior style. Decide how it will be shown, whether on a table or a plant stand.

It’s best to keep the terrarium in a dedicated space. Avoid moving it frequently, as changes in light intensity and duration may harm plant health. Find a location with bright, indirect light. Often, an eastern exposure with morning sun is ideal for terrariums. Similarly, a western exposure may work well if afternoon heat is avoided.

Avoid placing a terrarium close to a window, as solar energy can build up heat inside the container, potentially burning the plants.

Less Is More

Plant-supply departments often carry an array of terrarium supplies, which are also available online.

Beyond the container, decorative accessories can enhance the design theme. These items may be ceramic, glass, metal, or plastic—anything impervious to moisture. They can play a dominant or subtle role in the design, or they can be omitted to maintain a natural and uncluttered look.

This example uses heat-treated bark. Avoid using bark intended for outdoor landscapes, as it may harbor pathogens that could introduce disease into the terrarium. Heat-treated bark for indoor plants offers a nice alternative to moss or can be combined with it for pattern and texture. Similarly, it may be advisable to use only one variegated, fancy-leaved plant along with other green plants.

Horticultural-grade charcoal consists of pure carbon chips, about one-fourth of an inch long. This material provides a filtering effect for water that has percolated from the soil mix. You can also use aquarium charcoal, although it may be slightly more expensive. Only clean, washed gravel and sterile, soilless potting mix should be used.

Care and Display

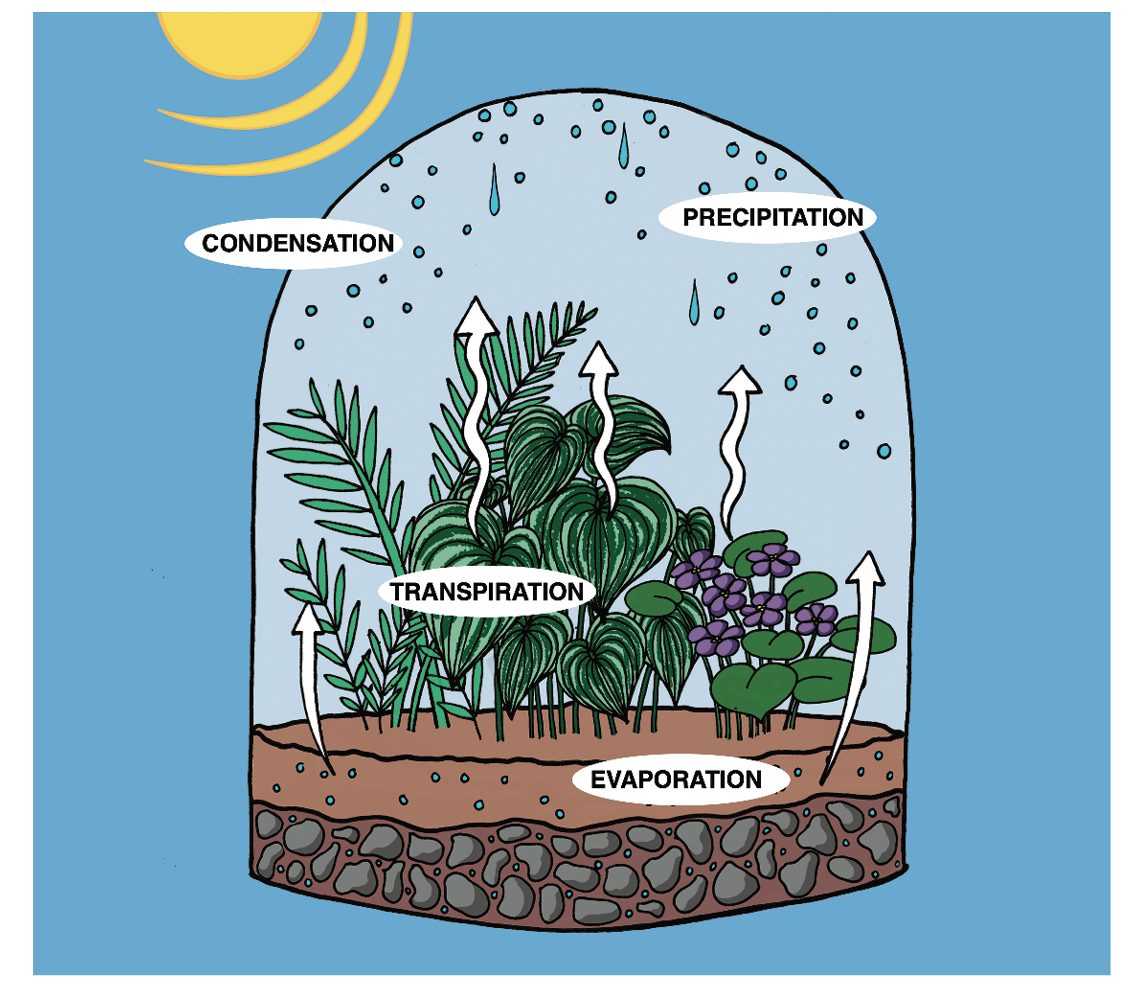

When water droplets (condensation) form on the inside walls or lid of the terrarium, open the lid for about an hour to allow excess moisture to evaporate. Continue this process until you see very little, if any, condensation. At this point, the terrarium ecosystem has reached equilibrium and can withstand long periods without additional watering—from weeks to years!

One goal of terrarium culture is to encourage slow growth, which reduces the need for pruning. Air, moisture, and sunlight aid in photosynthesis, which converts light energy into carbohydrates. This is all a terrarium needs to thrive. There is no need to add fertilizer to a closed system.

A terrarium typically has a display life of no more than one or two years. As plants mature, they may outgrow the container, necessitating pruning or removal. This is a great opportunity to refresh the design by rearranging existing plants or adding new ones—a fun and relaxing activity for any time of year!

Project Materials*

- Container (2-gallon glass jar)

- Plant selections (Neanthe bella palm, nerve plant, Boston fern ‘Fluffy Ruffles’)

- Finely chopped, heat-treated bark

- Gravel

- Horticultural-grade charcoal

- Potting mix

- Moss (undyed sheet moss)

- Decorative items (miniatures, shells)

- Mist bottle and water

- Scissors or snips

- Newspaper or other paper

*Not all materials are necessary for every project. Plant supply departments often carry a variety of terrarium supplies, which are also available online.

Steps

- Water the plants in their original pots a few hours or the day before construction. Be sure to wash the terrarium container before using it. Lay down a few layers of newspaper on your work surface for easy cleanup.

- Add 1 inch of gravel to the bottom of the container.

- Make a funnel with two or three layers of newspaper or other paper. Using the paper funnel, slowly add about ¼ inch of charcoal.

- Next, add about 2 inches of soil mix to the container. Create a hole in the soil large enough to accommodate the plants’ root balls.

- Remove plants from their pots and carefully break up the soil at the top and bottom of the root ball.

- Often, there are multiple plants of the same variety per pot. Carefully open up the root ball with your fingers to separate plants into smaller pieces.

- You may need to prune a few leaves or stems if they touch the sides or lid of the container.

- Place the tallest plants toward the center and the remaining plants around the center. Allow a bit of space between them. Evaluate the need for additional pruning.

- Add the plants and tamp down the soil around the rootball.

- Now, it’s time to water the terrarium. Using a mist bottle, mist the interior sides of the glass jar. This not only provides moisture to the soil but also helps wash charcoal dust or other organic materials from the glass. You can tell the soil is moistened when its color appears saturated. Be sure to mist the root ball area of each plant heavily, but do not fully saturate the soil. Water can always be carefully added to the terrarium, but it cannot be drained from it.

- Break up large pieces of moss and add them to the soil surface in patches. Add chopped bark to other patches. Finally, add decorative items.

To establish the moisture balance within the terrarium, follow these steps:

- After finishing the project, leave the container open for about 24 hours to allow excess water vapor to escape.

- Replace the lid for 24 hours.

- Remove the lid for another 24 hours, allowing condensation to evaporate.

- Replace the lid again for another 24 hours.

Repeat this process until no moisture collects on the inside glass of the terrarium. At this point, the terrarium has reached equilibrium and will not need watering for weeks, or even months.

Foliage or stems resting against any interior glass surface can harm the health of the leaf, plant, and the entire terrarium system. The leaf surface gives off water vapor; if it is near the glass, moisture will be trapped, creating an environment conducive to disease. Similarly, it is best to keep plants from touching each other to prevent the rapid spread of disease.

Plants (Cacti and Succulents) Suitable for Open-System Terrariums

- Aeonium

- Aloe vera

- Burro’s tail

- Cactus

- Crown of thorns

- Devil’s backbone

- Echeveria

- Flaming Katy (Kalanchoe)

- Hens and chicks

- Jade plant

- Panda plant

- Pencil plant

Plants Suitable for Both Open- and Closed-System Terrariums

- African violets (including miniature African Violets)

- Anthurium (miniature varieties)

- Ardisia

- Artillery fern

- Baby’s tears

- Bead plant

- Creeping fig

- Croton

- Dieffenbachia

- Dracaena

- Dwarf schefflera

- Fern

- Flame violet

- Gold dust Dracaena

- Ivy

- Lipstick plant

- Maidenhair fern

- Nerve plant

- Norfolk Island pine

- Orchid (such as miniature

- Phalaenopsis)

- Palms

- Peperomia

- Philodendron

- Pilea

- Plumosa fern

- Pothos

- Purple velvet plant

- Rabbit’s foot fern

- Rex begonia

- Selaginella

- Spider plant

- Strawberry begonia

- Tillandsia

- Venus fly trap

- Zebra plant

References

Carloftis, J. (2006). Beyond the windowsill. Franklin, TN: Cool Springs Press.

DelPrince, J. (2013). Interior plantscaping: Principles and practices. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar.

FTD Fresh. (2017). Twenty popular types of succulents.

Hessayon, D. (1998). The house plant expert. Transworld Book.

Martin, T. (2009). The new terrarium. Clarkson Potter.

Pleasant, B. (2005). The complete houseplant survival manual. Storey.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 3253 (POD-09-24)

By James M. DelPrince, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, and Gary Bachman, PhD, Extension/Research Professor Emeritus, Coastal Research and Extension Center.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.